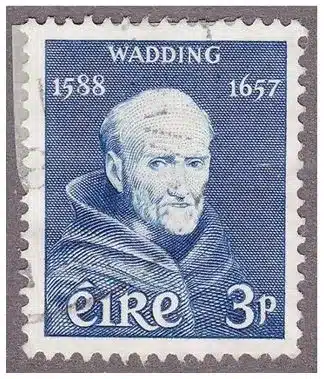

Most of us in Waterford know of Luke Wadding, the Irish man who was almost Pope and the founder of St. Isidore’s College – but did you know that it is Luke Wadding that we must thank for St. Patrick’s Day?

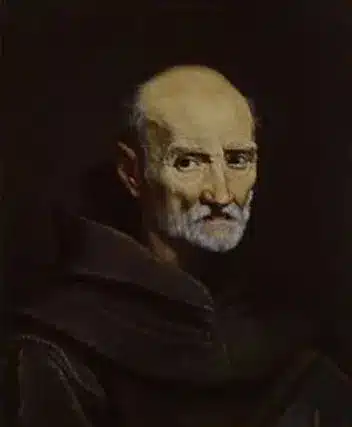

Born (on October 16th, 1588) and raised in Waterford, Wadding’s family were important merchants and on his mother’s side the Lombards were an old English family (with roots in Lombardy, Italy) who had been Mayors and influential figures since the foundation of the city.

Religion was important to this Catholic family and no less than five of his brothers became Jesuits, probably inspiring young Luke to do the same. He was a very bright child and probably owing to the wealth and connections of his family, he gained proficiency in Latin early-on and joined the Society of Jesus in 1601. However, when he was just fourteen years old, tragedy struck.

In 1602, an unknown plague swept through Waterford and among its victims was Wadding’s mother: Anastasia Lombard.

In those days, fear of disease and a lack of knowledge about the mechanisms of illness meant that even the bodies of the deceased were feared, and despite her important place in Waterford society, Anastasia had to be buried outside the city walls along with the rest of the victims.

In the aftermath of his mother’s death Wadding accompanied his brother Matthew to Lisbon and there he joined the Franciscan Friars. It is possible that his interest in joining the friars had first been sparked by spending time around Greyfriars in Waterford, which was then the Holy Ghost Hospital, a place for charity and medical treatment ministered by friars, despite the law prohibiting this.

Wadding’s studious nature suited the work of the friars and while he joined to get involved in charity, fate had other plans for him.

He was ordained in 1613 and quickly became one of the most respected and well-known Franciscan theologians at work in mainland Europe. From the first days of his career, Hugh O’Neill the exiled Earl of Tyrone – attempted to convince him to become part of the Irish mission but Wadding’s superiors were sure that his future lay in education.

He taught at Louvain, the Jesuit College at Utrecht and theology at the University of Salamanca.

He eventually moved to Rome and this is where our story begins. Wadding never forgot his Irish roots and upon his arrival in the Eternal City, Wadding saw the need for a centre of education for the Irish in Italy.

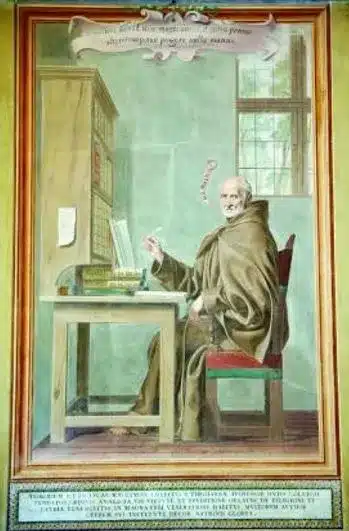

Due to religious persecution in Ireland, many young Irishmen went abroad to gain a Catholic education but in Rome, their needs were largely ignored. The Franciscan Minister General gave Wadding a small, unfinished church and convent which was saddled with debts in order to accomplish his goal, but Wadding took charge of it anyway and set to work establishing St. Isidore’s into a school worthy of his fellow Irish Franciscans.

Wadding installed a huge and important library in the college of manuscripts dating as far back as 1400. In St. Isidore’s he also betrayed his first fondness for St. Patrick when he installed him as a co-patron saint of the college.

Later Wadding would lend his support to the 1641 uprising of Catholics in Ireland and allegedly sent arms and men to Ireland to help the cause. He also persuaded the Pope to send Archbishop Giovanni Rinnuccini, though even with the men, arms, money and 20,000 pounds of gunpowder, the effort was a failure.

Nevertheless, Wadding remained a popular figure in Rome. There were attempts to make him a cardinal, though they never came to fruition – however, he did receive a number of votes in the election of a new pope, making him the only Irishman to ever get close to such glory. However, it is his work on the calendar of saints which makes him important to us all today.

It is widely held that after he established his reputation in Rome, the Pope himself asked Wadding to lend a learned eye to helping to create a comprehensive calendar of saints. Wadding completed his task dutifully but thanks to his patriotism, along with all of the well-known Saints like Anthony and Francis, Wadding snuck in an extra, slightly lesser-studied Irish Saint – Patrick.

March 17th had long been observed by the Irish as St. Patrick’s Day, but only when Wadding gave church sanction did it become a huge spectacle of parades and céilithe. One of the places integral to the international importance of St. Patrick’s Day – and to its status as a national holiday – was Waterford.

In February 1903, before the 17th of March was ever made a national day of celebration, a meeting was held in the Town Hall in Waterford where the citizens unanimously voted to make St. Patrick’s Day a ‘general holiday’ where local businesses would close in order to allow everyone to celebrate.

Strangely enough, this included all of the local pubs, which hardly seems in the spirit of the modern holiday. The ‘patriotic movement’ to declare the day a ‘National Holiday’ must have been a success as later that same year it was declared a national holiday under the Money Bank (Ireland) Act.

Words: Clíona Purcell