History of St Patrick

Roman Britain

History

Following his conquest of Gaul, Julius Caesar led two legions to Britain in 55 BC. In 54 BC he returned with five legions believing the land to be rich in silver.

Caesar’s expeditions had limited success and it wasn’t until 43 AD that Claudius established a stronger presence which would continue to grow for two centuries. The conquest however would never be complete, northern Caledonia in particular, would remain both wild and remote as would Hibernia, an island to the west.

The Roman Empire’s presence in Britain began to dwindle in the latter half of the 4th century, the growing menace of Germanic barbarian tribes, amongst other factors, precipitated the contraction of Roman influence.

History

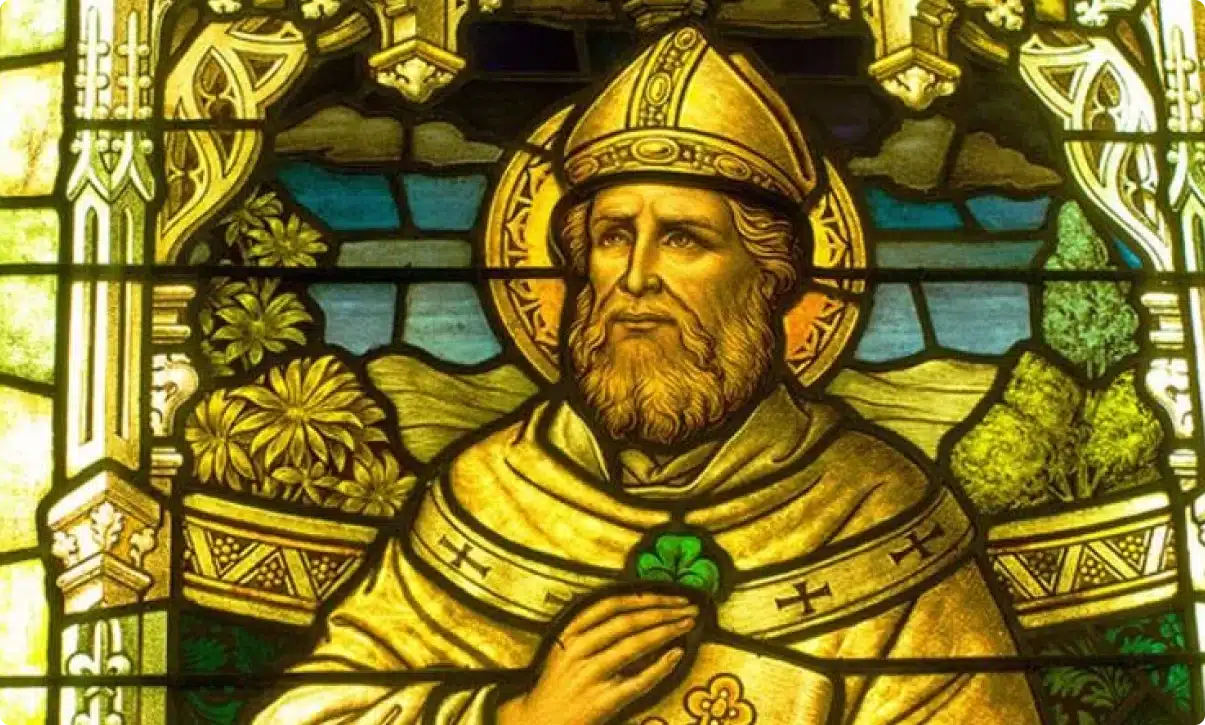

The Man Behind the Legend

History

Early Life and Captivity

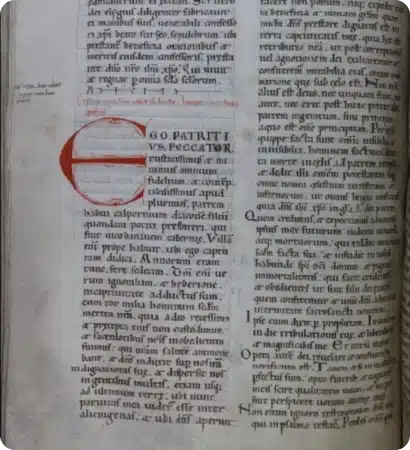

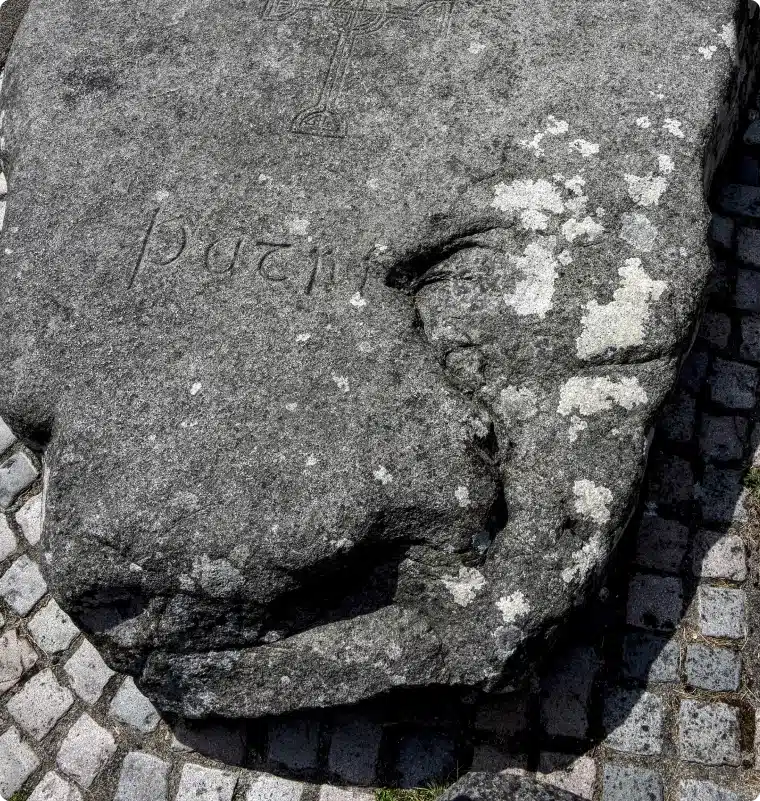

Patrick left two documents written by his own hand – ‘Confessio’ and ‘Epistola’ – that give great insight into his character. In ‘Confessio’, Patrick tells us: ‘My father was Calpornius.

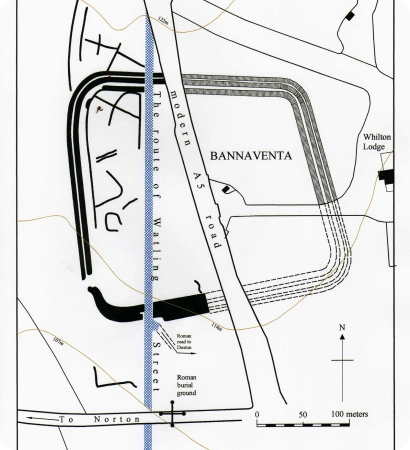

He was a deacon; his father was Potitus, a priest, who lived at Bannavem Taburniae. That is where I was taken prisoner.’

Young Maewyn (Patrick’s birth name) was kidnapped and enslaved in Ireland. The collective trauma of kidnap, separation, isolation and hardship tending livestock in the wild caused a spiritual awakening in the youngster.

He believed that his abduction was a form of divine retribution for his initial lack of faith.

history

Return and Mission

Maewyn escaped from captivity and found passage back to Britain where he was reunited with his family. They welcomed him as a son and pleaded with him never to leave them again. However, he claims that he was summoned through dreams to walk among the Irish once more and spread the word of God. Upon returning home to Britain, Maewyn decided to devote himself to the service of God and the study of Christianity. It was at this point that he adopted the name ‘Patricius’ meaning father figure.

Sources and suggested further reading

B. McCormack, ‘Perceptions of St. Patrick in Eighteenth-Century Ireland’ (Dublin 1998).

T. Cahill ‘How the Irish saved civilisation’ (Sceptre Lir 1995).

J. Duffy ‘Patrick in his Own Words’ (Dublin, 2000).

T. O’Loughlin ‘Discovering St. Patrick’ (London, 2005).

C. Mohrmann ‘The Latin of St. Patrick: Four Lectures (Dublin 1961).

M.B. De Paor ‘Patrick, the Pilgrim Apostle of Ireland: An Analysis of St. Patrick’s Confessio and Epistola (Dublin 1998).

D. Howlett, The Book of Letters od St.

Patrick the Bishop (Dublin 1994).

D. Conneely St. Patrick’s Letters A Study of their Theological Dimension (Maynooth 1973).

Research compiled by Johnny Codd

history

The True Legacy

The actual legacy of St. Patrick is not necessarily the introduction of Christianity to Ireland, nor the intangible mythologies that surround him. The fortuitous timing of when Christian doctrine arrived is perhaps the key. As the Dark Ages descended on Europe, Ireland earned its reputation as ‘the land of saints and scholars.’

The guardianship of classical texts, both Roman and Hellenistic, coupled with an appreciation of knowledge and education became the defining characteristics of the Christian establishment in Ireland. Irish monasteries safeguarded literary treasures while barbarian tribes pillaged Europe, leaving little trace of Greco-Roman literature.

history

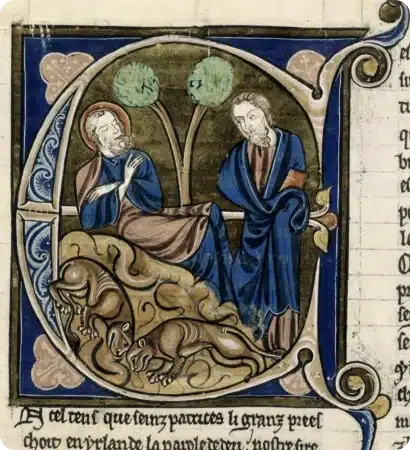

Myth and Reality

St. Patrick became quite the hero in Irish folklore, and the famed Celtic storytelling tradition played a significant part in weaving the wondrous tapestry of these tales. The church policy, when unable to deconstruct the pagan belief system, was to simply integrate the Christian message into existing folklore – a case of ‘if you can’t beat them, join them.’

It is interesting to note that neither ‘Epistola’ nor ‘Confessio’ mention shamrocks, snakes, Paschal Fire, or King Loíguire. The only supernatural events mentioned are the messages received through dreams. There are many strange myths and legends associated with St Patrick, so as Hamlet might say “therefore as a stranger give it welcome, for there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophies

we had some craic’

Real Tales from Leprechaun Believers

Vibrant Atmosphere

Attending the St. Patrick’s Festival in Waterford was an unforgettable experience! The vibrant atmosphere, filled with music and laughter…

Megan Taylor

London

Diverse Events

I loved the diverse events, from the colourful parade to the engaging workshops. It was a perfect celebration of culture and joy!”

Mike Fairbanks

Derry

Full of Energy

The parade was vibrant and full of energy, especially the spectacular performance by the local dance troupe.

Trev & Lisa

USA

Local Culture

Watching the little ones explore the local culture and join in the festive fun with friends and family was a joy. We’re already counting down to next year!”

Joanne & Family

Leeds

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

Frequently Asked Questions

The city is easily accessible for families to enjoy the festivities. We are here to help, with any questions.

What are the dates for the St. Patrick's Festival Waterford?

The festival runs for four fun-filled days, typically starting before St. Patrick's Day.

What time do the main events begin each day?

Events and activities generally run throughout the day and into the evening.

- Day 1 (Friday): Events usually kick off in the evening, with walking tours and ticketed performances starting around 6:30 pm and live music continuing late.

- Day 2 & 3 (Saturday & Sunday): Daytime activities, workshops, and markets often start around 10:00 am to 12:00 pm. Live music and street performances continue through the afternoon and into the evening.

Day 4 (Monday – St. Patrick's Day): The main St. Patrick's Day Parade starts at 1:00 pm sharp. Daytime workshops and the city fairground typically begin around 10:00 am to 12:00 pm.

Where can I find the full Programme of Events?

The full schedule detailing locations and specific times for each day can be found on the festival's dedicated Programme of Events page.